As a joint venture, “Keywords in Play” expands Critical Distance’s commitment to innovative writing and research about games while using a conversational style to bring new and diverse scholarship to a wider audience.

Our goal is to highlight the work of graduate students, early career researchers and scholars from under-represented groups, backgrounds and regions. The primary inspiration comes from sociologist and critic Raymond Williams. In the Preface to his book Keywords: a vocabulary of culture and society, Williams envisaged not a static dictionary but an interactive document, encouraging readers to populate blank pages with their own keywords, notes and amendments. “Keywords in Play” follows Williams in affirming that “The significance is in the selection”, and works towards diversifying the critical terms with which we describe games and game culture.

Please consider supporting Critical Distance at https://www.patreon.com/critdistance

Production Team: Darshana Jayemanne, Zoyander Street, Emilie Reed.

Audio Direction and Engineering: Damian Stewart

Double Bass: Aaron Stewart

Darshana: You’re listening to Keywords in Play, an interview series about game research supported by Critical Distance and the Digital Games Research Association.

As a joint venture, Keywords in Play expands Critical Distance’s commitment to innovative writing and research about games while using a conversational style to bring new and diverse scholarship to a wider audience.

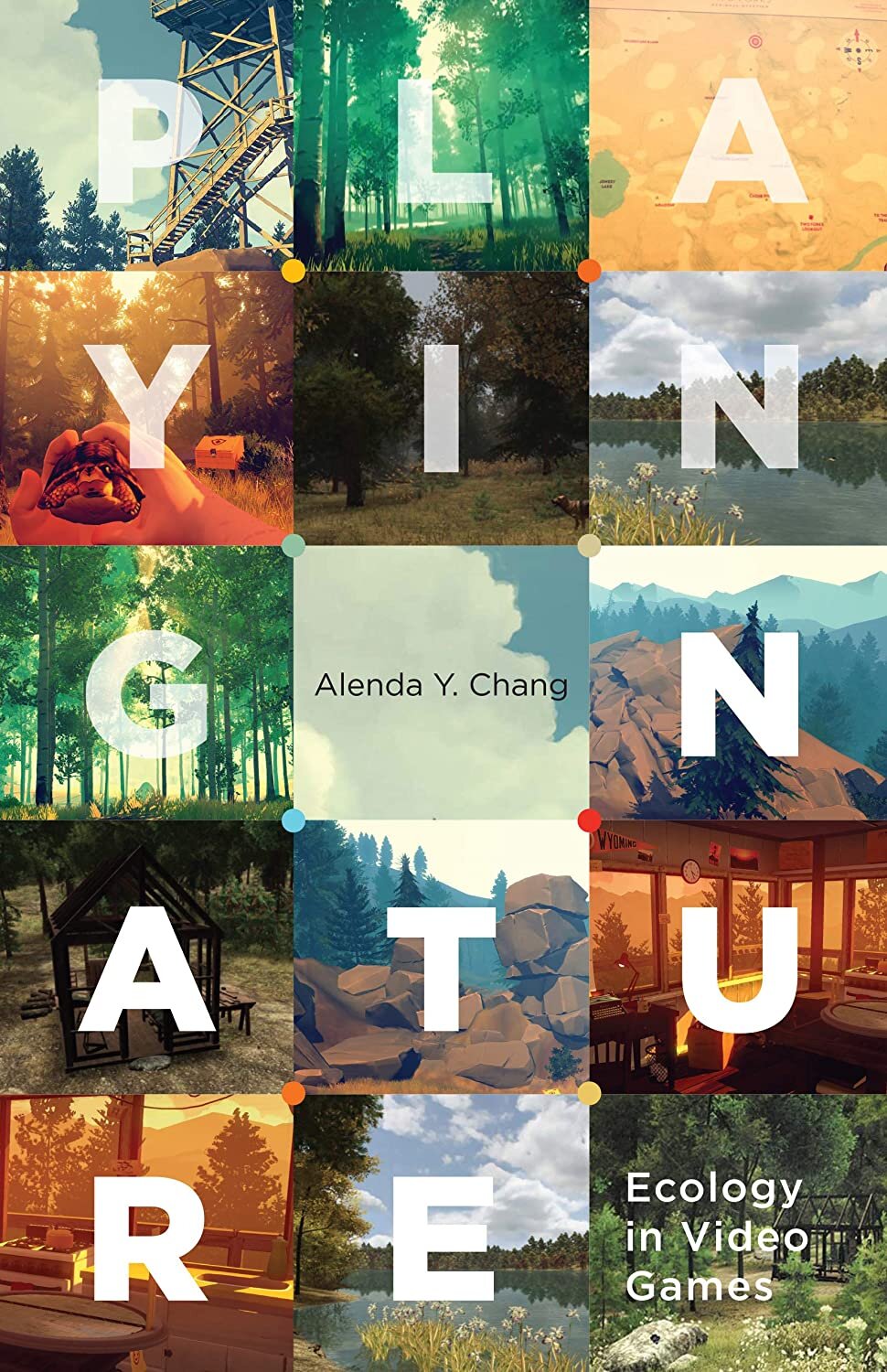

Emilie: Welcome back to Keywords in Play. In this episode, I’m talking to Alenda Y. Chang, who is an associate professor of Film and Media Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research and teaching interests include environmental media, histories and theories of the digital, game studies, science and technology studies and sound studies. And her articles have appeared in numerous journals, among them interdisciplinary studies in literature and environment, and feminist media histories. And her first book ‘Playing Nature: Ecology in Video Games’ is what we’re talking about on this episode. So, I was really interested in just the structure of the book and how much ground it covers.

Alenda: Oh, thanks, Emilie.

Emilie: Yeah, it’s really fun to read. And I enjoyed how it really approaches, you know, the ecological perspectives on games from a lot of angles. And one of the first examples that you use when you’re introducing the idea of looking at games, as you know, ecological is the concept of an ecological text or ecocriticism, which is drawing from literary studies. So, I guess, just to kind of give people a feel of what the books about, could you describe how you apply this concept to something that, you know, like a video game or like a digital environment is not really straightforwardly textual?

Alenda: Yeah, that’s a great question. It actually kind of maps my background too, because I guess people probably don’t realize that I kind of cut my teeth on literary studies. So, I was really into Shakespeare and creative non-fiction. And so, I was an English major, as well as a bio and film major. And then I did a master’s in English and a PhD in rhetoric. So, my kind of course was from a very, you know, conventional medium of print, and, and the literary through to film, which I fell in love with, and was sort of obsessed with documentary and production and all this other stuff, and then found my way to New Media Studies, which, for me, was a natural home because of my hobbies. So, having sort of grown up with the Internet, and, you know, using really early computing devices, and internet services, like bulletin board systems, you know, and modems, dial-up modems, you know, I had kind of had this course, and my first jobs out of college, you know, I didn’t go back to school right away, I actually worked in the tech sector for internet startups, in the late 90s, early 2000s. And so, for me, like kind of heading into digital media studies, or digital humanities, which was called for a very long time still is in some sectors, it just made a lot of sense. And so, what happened is, I was participating in this graduate working group called ‘Mediating Nature’. So, it was convened by a student from English and a student from, I think, geography and what I realized in doing all this reading, that was primarily in literary ecocriticism, which is where a lot of environmental criticism has developed, because there’s, you know, hundreds of years of nature writing and, and sort of, like poetry and, and fiction and non-fiction about the human relationship to the natural world. What I realized was that, boy, there’s this really, you know, diverse, rich, intellectual tradition within this domain, but that none of it was crossing over to, say, new media studies, and specifically game studies, which I was just starting to get interested in. And having play games all the while, and, you know, I think I kind of latched on to this weirdness and found that there was a nugget there to be explored and that a lot of the rhetoric was actually about how the two could not mix. So, a lot of environmental theory was about privileging, you know, sort of direct or unmediated access to the natural world. You know, but the irony there is that a lot of it was happening through writing. And people were smart enough to point that out, like how odd you know, that you’re writing about this and trying to evoke it. And then video games, on the other hand, are seen as this really artificial, and in some ways, like sacrilegious. To say that video games could embody natural experience is somewhat heretical. I think for a lot of environmental educators who really want that unmediated direct access to the outside, right? So, I thought, hey, this sounds like it’s gonna be a fun fight. Let’s, let’s take this on. And let’s also, let’s port, these very rich discussions that are happening within what they would have called first wave, literary ecocriticism, where it’s primarily about texts over to these new domains. And I think environmental criticism has definitely broadened since then, and has started to think a lot about cinema, and then less so, but increasingly also, thinking about interactive media. So, that’s, that’s kind of where we’re at. And I’m hoping that my book opens up that direction, and people can run with it, disagree with it, do whatever they want with it, but I just would love to have the conversation, get started.

Emilie: The examples of the games that you kind of, say can be analyzed from like the ecocriticism, the very literary angle, that’s sort of like ones that are very much about like an experience or set in a specific place. So, I think the example I remember is like Firewatch, and, you know, being, you know, the person watching for wildfires in that very specific area. Later, you also, kind of address games that maybe have a more, you know, ambiguous or less deliberate relationship to the environment, or also, like ones that kind of presented as a blank slate, so I’m kind of thinking of the simulators, or like, God games that kind of allow you to, like, summon environmental disasters, or allow you to kind of like set up this very, you know, kind of unrealistic sense of a totally controllable environment. You said that, like, you know, there is kind of a resistance to like, saying, video games can represent nature, you know, because it’s kind of like, worse than going outside, you know, it’s kind of the argument. But also, yeah, it does kind of have to balance the issue of like, the expectation that the player is, like, powerful and can affect these things, versus caring for the environment, or, you know, kind of observing it, which is much more often hands-off.

Alenda: That’s another good question. I’ve wrestled a lot with, you know, questions of realism and representation, you know, but also, like you’re saying, with these questions of agency and scale. First, the caveat that, you know, I think all game scholars have to give is that we don’t play all games. First of all, we have certain genealogies, you know, that we kind of grew up with are conversant with. So, I hesitate to speak for all games and all players. But you know, in my experience anyway, in the book, I really tried to kind of have it both ways, which is, which is tough, which is, you know, to both have games, where you’re mostly observing and looking like in a walking simulator, which has its own uses, right, where you’re kind of more of a kind of a naturalist gaze or, you know, games where you have very little agency. And maybe, in fact, you feel like that the natural world within the game, or even the built environment, I don’t want to make too harsh a distinction, but, but that somehow the games environment, or AI, has more agency than you. And then some ways that could be very humbling. And so, I like that, but I don’t think that has to be everything. And that’s why actually the God games and the simulation games, which I used to play, I remember I played Populous wasn’t a huge Sim person, but you know, did some of the other Sims. And those games, even though like, you can certainly level the critique of like, you know, like the heroist God trick and like the sort of aerial surveillance view and sort of society of control that kind of stuff. I think that’s there. But at the same time, it’s, you know, I tried to say that, that perspective, can be really illuminating when paired with other perspectives because it is largely a planning perspective. It is a kind of a larger, systemic perspective. And in some ways, for, you know, wicked problems, like climate change, and other things, we kind of need the gamut of, you know, direct experience, kind of like lived experience, as well as the larger regional planetary views, right, in some ways, I think, I think, you know, people like Ursula Heise, have said, like, there’s a real failure to think big, which has kind of been a cost of espousing the local and really thinking like, about the local, and that we really need also, need the global scale. And so, you know, those games, they’re not perfect, but they, they allow sort of a different level of interaction, which I think is useful, even if it’s instructive in negative ways. Like with ‘Spore’ and how you can basically fix climate with technological doodads and wizardry, which I don’t, I’m not a huge fan of, but it’s still, you know, provokes you to think about things like that. Yeah. So, it’s, it’s kind of both. I tried, you know, I think that every kind of game, even games where you’re doing a lot of environmental destruction, sort of have interesting consequences or things to think with.

Emilie: And I guess in addition to that, the book kind of goes on, you know, kind of presenting all these different ways of, you know, looking at ecological issues in games, and, you know, positive and negative, like you said, it can kind of be, you know, a really useful tool for thinking through these problems, or it can be, you know, kind of teach you exactly the wrong thing, which is, you know, oh, they’ll just be some magical gadget, you know, that just lets us reset the environment. And it’ll be fine. Right. But yeah, I think, I think relating to that, you also, kind of bring in the ecological perspectives of games, and how a lot of them are kind of, you know, built upon, you know, you go to the place, you extract the resources, and you know, they just kind of become, you know, these discrete little objects that you could move around. You relate that interestingly, for one thing to like, the trees that are developed and sold by, like, resource companies to games. That’s something that was really interesting to me. And I think I don’t have enough of like an ecological background to fully appreciate, like, what’s interesting about 3d, like, representations of trees. So, could you go like a little bit more into how you see like, ecological perspectives, expressed through like the 3d trees that appear and again,

Alenda: I love that you’re focusing in on the ‘SpeedTree’ stuff because I have a, I have a separate essay about them, and electronic book review, which I love and where I got to do this deep dive into plant philosophy and sort of like algorithmic botany, and all these kinds of questions of how digital asset models get created, and specifically vegetation. Right. And I think that might be where I’m heading for the next project, actually. I think what I was trying to get out there was, well, a few things. I think, as a media scholar, I’m really interested in kind of the increasingly stock nature of our visual landscapes that surround us in the form of computer-generated images, not just in games, because ‘SpeedTree’, even though one of its primary branches, the one that started with was for games, they also, sell to filmmakers and television producers, and architectural visualizers. You know, so, I think, you know, chances are, if you’ve seen, like a computer-generated, tree, or piece of vegetation, in a TV show, film, or blockbuster game, it’s, it’s from this company, right? There are there are competitors, but it’s definitely the main one. But of course, you know, even though they have, you know, I’m sure, you know, hundreds of employees industriously, working away, to create these assets and to build their libraries. And that, you know, people can tweak them and sort of hand model them to an extent, at the same time, that’s inevitably of a generic character, which I find really interesting. That led me to ask all these questions about sort of what assumptions get baked into those things. And even just very quick analysis of things like the Unity asset marketplace, where developers go to shop for pre-made assets, if they don’t want to lavish, you know, money or time on developing their own. It just, you know, looking at that shows me, you know, it’s very curious to see, well, a, like how many gun models are there compared to like animal models, right. And it turns out, like, there are way more like deciduous trees like North American temperate forest trees, the kind that you would expect living in the United States or Europe, there are way more of those than like, subtropical, broadleaf trees, right. And in some ways, the algorithms that these modellers use are better at modelling the branching kinds of trees, than the trees that take other forms. And so, there’s, there’s a lot of kind of going on here. There’s sort of the computer science, the graphical side of things, the botanical side of things, the corporate model of stock imagery, and that’s why I, you know, I referenced Getty and Corbis, and, and those kinds of like libraries of images of, you know, like, women eating salad. And you know, just like, the trick to stock photography is for it to be just anodyne enough that like, it can be ported into all these different materials without feeling abrasive. So, like, it’s a deliberately cultivated abstractness. If that’s what we’re also, getting when we wander a world like ‘Oblivion’, or you know, ‘Skyrim’, or something like that. What does that I’m just kind of curious about, like, what does that mean experientially for me as a player, but also, compounded over years? What does that mean for sort of my expectations of not only other virtual worlds but also, like the world that we actually exist in? Right, am I going to have that bizarre moment where I wonder if I go to a national forest or something and I’ll say, wow, I didn’t really think giant sequoias look like that. So, I’m just curious about this about the sort of imaginary that’s getting developed by these tools and their ubiquitous adoption. That’s kind of happening without our consciousness.

Emilie: Yeah, I think that that is like an interesting point about, as video games become, like, larger budget, like more kind of elaborate, you know, productions, their supply chains start to have a lot in common with, you know, like blockbuster films that kind of need, you know, especially now they kind of need like, all these 3d models to like, fill in the stuff that they can’t actually do, including trees now. Which you know, that…

Alenda: I think it’s a huge, it’s a huge issue for the industry. And that’s why some of the big players like EA are pursuing, like cloud-based solutions, or they can leverage, you know, worldwide networks of computers and machine learning and, and all this stuff, because asset creation has become exponentially harder. As these worlds like you’re saying, have grown more and more graphically, real, realistic, and complex, right? What’s interesting is it’s, it’s really, I’m really fascinated to see what we’re hurtling toward right now. For some, it’s VR for others, you know, it’s a low carbon future where we’re just not on our devices as much.

Emilie: Yeah, I guess that does kind of relate to the second to last chapter of the book that was probably my favorite, I really liked the chapter on entropy, cus…

Alenda: You’re into the darkness!

Emilie: Well I thought , I thought it was really cool and how it like bridged to the idea of energy use and E-waste and kind of all these issues that are tied up in terms of like, you know, how, how the videogame industry has basically, like, started as a consumer technology and just like, taken off and grown massively. And you relate it like metaphorically, I guess, metaphorically, and a bit literally, as well to how these games represent things like farming as like, you know, this process that like, has no waste, you know, it can just be done indefinitely. There’s no like long term consequences to just kind of, you know, finding like the thing that grows the fastest on your ‘Harvest Moon’ farm, and just like harvesting as much of it as possible. And in many ways, that’s kind of the way that you’re encouraged to play the game.

Alenda: Yes, yeah.

Emilie: It would be really interesting to kind of hear about, like, how you made that relation, and how you explore those issues as intertwined in that part?

Alenda: Yeah, I think oftentimes, when I give talks, I tried to tell people that the book actually kind of like fought with my editor about like, a tiny little word in the title, which was after the colon, its ecology and video games, right. But that’s because my editor said, just do that. But I really wanted it to be the ecology of video games. And, and I know that seems so, minor. But for me, you know, it’s, it is important, I think, to have the sort of content analysis of, you know, like, what kind of representations and, and mechanics or processes are being represented in the game, the book is largely about that. But I think it’s also, important to look at, like you’re saying, the supply chain and the production context, and not even just that sort of materiality, but also, the ways that games are just part of these wider assemblages, of, you know, the player contexts, the sort of environmental contexts, the labour context, or all these other contexts that kind of intersect. So, that’s, that’s a story of, you know, publication, kind of forcing you to be one thing, but that chapter grew out of this, this piece, I had written about farm games, where for a period, I was obsessed with them, and I think I played, it’s almost embarrassing to admit, but I think I’ve probably played like 70 or 80 of those games. And they’re all pretty much, they’re all pretty much the same, right? There are like some minor differences. Sometimes it’s magic. And sometimes it’s, it’s science, and others have these narratives about fighting global agribusiness. And it’s always about the valorization of like a family farm. And it’s almost always a female heroine. And we can you have the conversation about casual games and the sort of presumed market for those. But you know, for me, it was just really, it was around the time that ‘Farmville’ was really popular, and those Zynga games that were supposed to be social, but were really kind of anti-social. And yeah, so, there was no you know, there were some Chinese games and Japanese games and others that were really also, even more popular. So, I was really interested in it because the other the ways they’re just these really direct similarities I think you were hinting at between the ways that global agribusiness treats nature or you know, animals, and plants and soil and all those other things in the same ways that sort of computers also, treat game assets or game objects, right? It’s this kind of monocultural thinking, right? And there’s, there’s really not necessarily a good reason it has to be like that because there are all these other kind of forms of much more healthy farming, like ‘Three Sisters Farming’ that’s pursued by Indigenous communities around the world where nutrients get replaced by, you know, these this kind of symbiotic interaction of different species, it kind of made me tear my hair out a little bit to play ‘Farmville’, and then, you know, harvest my pigs for bacon, and they were unharmed afterwards. So, I like to, you know, when I’m, when I teach, these are something I will I like to put those kinds of games next to like the PETA, the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, the kind of activist parody games that they make, because they tried to do the exact opposite, where they really highlight for them, you know, the cruelty and the kind of inhumane conditions around eating animals or something like that. So, it’s just fun to kind of like put those together. Like they have PETA’s ‘Cooking Mama’, which is mama kills animals where yeah, they up-end the Nintendo aesthetic by making it really gory and squelchy, and, you know, when you’re preparing recipes, and the same thing has happened in cooking shows, right and used to be that Julia Child would actually like eviscerate a chicken and bone it and, you know, now it’s like, oh, I’ve got these, these like pre-wrapped chicken breasts that magically came out of the fridge and has been placed there by my production assistant. That sort of stuff. So, you know, there are all these trends that I think actually are traceable across media, which is fun. And then the farm games itself grew into this larger consideration of, you know, do games adequately model things like waste, you know, waste and human and natural labour. And kind of just like the unsightly unpalatable aspects of existence that are nevertheless, still there. And, you know, that could be everything from the sort of, you know, child labour and resource extraction of minerals that cause, you know, resource conflicts and other parts of the world. So, that we can have our PlayStations you know, that sort of stuff, all the way to all these mechanics as players we just take for granted. Right? Like the fact that we can stick a million things in our backpacks.

Just these little things are like infinite supplies, right? Like, if you play an MMO or a lot of games, they’re essentially infinite resources. Not all obviously, but all of these little sort of things that sort of are there for player convenience and enjoyment. You know, it just, you start to question it after a while.

Emilie: Yeah, I mean, I guess this is this is kind of a bit of a throwback, but I always think about, like, how one of the activities that you had to do so, much of in ‘Runescape’ was just like cutting down trees for no reason. Like your, your chopping skill, or whatever.

Alenda: Oh, my goodness.

Emilie: I just I just remember, like, you just kind of stand at the same tree and just like chop it down like 100 times and that would be, you know, your, your activity for the day. Yeah, but yeah, it is really, you know, kind of strange in that. I definitely feel like, you know, there is this kind of thing that people like, have been especially talking about recently with, like, the way that electronics are like less repairable. And they’re kind of more mysterious about, like, what goes into them and what you do with them, like after they break, that is kind of like the same mystery in terms of like, why are these items infinite? And like, why can I just like, do this action over and over and over again? And, you know, there’s no waste product, there’s no pollution, anything like that happening?

Alenda: Yeah, I mean, I think my work since ‘Playing Nature’ came out has been a sort of turning a little bit more not quite quantitative side of things, but like, trying to work more with industry and with journalists and others to think about these kind of broader implications of the game industry. And I’m not an engineer or anything like that. I’m not somebody who’s an expert on calculating carbon footprints or anything, but there’s a lot of great work that’s being done about this. Like Benjamin Abraham’s work, and I’ve been working with the IGDA, the International Game Developers Association, they have a climate special interest group, which has been active and just trying to get going and in terms of like, how do we, as an industry kind of confront the issue of climate, whether that’s through game content and certain kinds of design patterns, or, you know, establishing councils at every major game company, or like a Sustainability Officer which exists in some places. So, yeah, I mean that I find myself in this interesting position of being somebody who’s really a scholar and somebody who writes and thinks, to now being somebody who now has to sort of talk about these things with, with press and with actual workers in the game industry and, you know, trying to create ways to, to change for the better. Like I just finished a, I actually just submitted this chapter about cloud gaming that I’ve was writing with a co-author, Jeff Watson, who unfortunately passed away. We were very much interested in looking at this, the future of gaming, if you believe Google Stadia, whether or not that was actually, like a better option for gamers in terms of sustainability, and, and all these other things like energy consumption and device ownership and right, ‘cus if you listen to them, it sounds like it’s perfect, ‘cus you don’t have boxes, and you just, you know, you don’t need to buy a specialized device.

Emilie: Yeah, but it’s always just sitting somewhere else.

Alenda: Right, right. Exactly. It’s somebody else’s box, in a big warehouse of boxes.

Emilie: Yeah, I do think that is such a complicated question. Because there is like, so, many, like moving parts to it, it’s like, okay, well, you know, we don’t have to ship an individual console to everyone. But at the same time, the amount of data that’s used to like, kind of keep these things live all the time, you know, that might be more power than someone just running it locally. So, yeah, it’s, it seems…

Alenda: Yeah, it took it turns out that it depends on all those things. So, there’s no straight answer of like, what is the best, most sustainable way to game? Because it literally depends on the game you’re playing, like, what its file size is? It depends on how long you’re playing it. It depends on when you’re playing it, where you’re playing it. Right? There’s so, many factors. It’s also, what device are you playing it on? And so, you know, and it’s so, murky, you know, one thing I’ve noticed is that a lot of the attempts to monitor E-waste, totally left out game devices, just because it’s such a massive problem, that they were too busy tracking, like personal computers from schools or something like that, or they just had to leave out all this other stuff. And when they did start to track it, they realized, wow those companies are actually doing a really terrible job, right? Fortunately, there are some groups that are now doing this kind of research. And so, they can find out that, you know, like gaming in California, where I live, takes as much energy as like 10 million full-size refrigerators every year, right? People are starting to do this, and you can start to wrap your head around the scale.

Emilie: Well, that was super interesting. And thank you for talking with us about your book. Is there like any online or social media place that people can find you or any upcoming publications to shout out?

Alenda: Well, you know, I kind of I am on Twitter very sporadically. I’m the worst social media like content creator, but I am on Twitter as gamegrower in just one word. And I, like I said, I think I got a couple pieces coming out one on cloud gaming. And I think there’s a upcoming conference on eco games that’s happening in the fall. So, there will be a publication, an edited collection coming out about eco games sometime next year, I think.

Emilie: All right. That’s really interesting. And I’m sure people want to keep an eye out for that. Thank you so much!

Alenda: Thank you for having me. Thanks, Emilie!

Darshana: We hope you have enjoyed this episode of Keywords in Play. For more great ideas around games check out criticaldistance.com. Or take a dive into the DiGRA archives at DiGRA.org.